The Critical Role of Heat Sink Housings in Modern Electronics

In the realm of high-power electronic applications, from server processors to electric vehicle inverters, managing thermal energy is not merely an afterthought—it is a fundamental design constraint that dictates performance, reliability, and longevity. At the heart of an effective thermal management system lies the heat sink, a component dedicated to dissipating unwanted heat. However, the heat sink alone is not a complete solution. Its efficacy is profoundly influenced by its enclosure, the heat sink housing. This housing serves as the critical interface between the heat-generating component, the heat sink itself, and the surrounding environment. A poorly chosen housing can cripple the performance of an otherwise excellent heat sink, leading to thermal throttling, reduced efficiency, and premature component failure. Therefore, selecting the optimal housing is a multi-faceted engineering decision that requires a deep understanding of materials, mechanical design, airflow dynamics, and integration specifics. This article delves into the essential criteria and considerations that engineers and optimization specialists must evaluate to make an informed selection, ensuring that the thermal solution meets the rigorous demands of high-power applications.

Core Material Selection: Balancing Thermal and Mechanical Needs

The choice of material for a heat sink housing is the primary determinant of its thermal performance and structural integrity. The debate often centers on the classic comparison between aluminum and copper alloys, but other factors like manufacturability, weight, and cost play equally important roles.

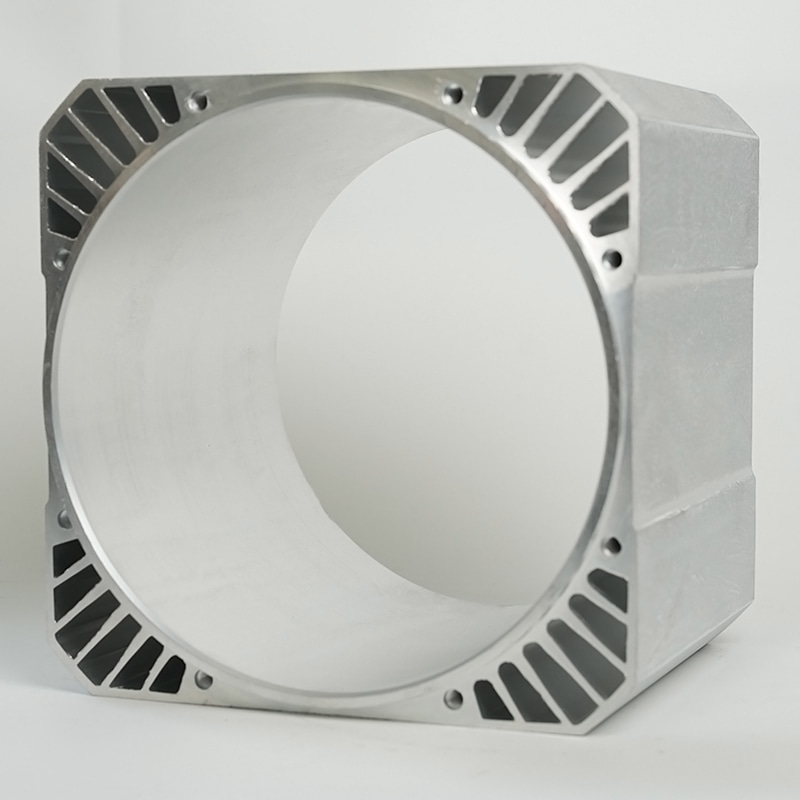

Aluminum Heat Sink Housing Design for Power Electronics

Aluminum stands as the most prevalent material for heat sink housings in power electronics, and for good reason. Its popularity stems from an excellent balance of properties. Aluminum alloys, particularly the 6061 and 6063 series, offer good thermal conductivity—typically around 160-200 W/m·K—which is sufficient for a vast array of applications. More importantly, aluminum is exceptionally lightweight, contributing to lower overall system weight, a critical factor in automotive and aerospace applications. Its natural corrosion resistance, due to the formation of a protective oxide layer, enhances durability without requiring heavy plating. From a manufacturing standpoint, aluminum is highly malleable and well-suited for cost-effective processes like extrusion, which allows for the creation of complex, custom profiles with integrated fins in a single operation. This makes aluminum heat sink housing design for power electronics highly versatile, enabling designs that can be tailored for specific board layouts and spatial constraints. Furthermore, aluminum housings can be easily machined, anodized for improved surface radiation and electrical insulation, or coated to meet specific environmental requirements. The relatively low material cost combined with efficient manufacturing pathways makes aluminum the default, high-value choice for many high-power scenarios where extreme thermal density is not the sole overriding factor.

Copper and Composite Alternatives

While aluminum is the workhorse, copper and advanced composites serve critical roles in demanding niches. Copper's undisputed advantage is its superior thermal conductivity, nearly double that of aluminum at approximately 400 W/m·K. This makes it ideal for applications involving extremely high heat fluxes or where the footprint of the thermal solution is severely limited. A copper housing can pull heat away from a hotspot more rapidly than aluminum. However, this advantage comes with significant trade-offs. Copper is substantially denser and heavier, often by a factor of three, which can be prohibitive for weight-sensitive designs. It is also more expensive both in raw material cost and in processing, as it is more difficult to extrude and machine. In practice, this often leads to the use of copper in strategic ways, such as copper bases or heat pipes paired with aluminum fins—a hybrid approach that leverages copper's conductivity where it matters most while controlling cost and weight. Advanced composite materials, such as aluminum-matrix composites reinforced with silicon carbide or graphite, are emerging to bridge the gap. These materials can offer tailored thermal conductivity, sometimes even anisotropic (directionally biased), and a coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) that can be engineered to better match that of semiconductor materials like silicon or gallium nitride, reducing thermal stress at the interface.

Copper vs Aluminum Alloy Heat Sink Enclosure Thermal Conductivity: A Detailed Comparison

The choice between copper and aluminum is fundamentally a trade-off analysis centered on thermal conductivity versus other system constraints. To state it plainly: Copper is a better thermal conductor, but aluminum is often a better system-level material. The following table encapsulates the core of the copper vs aluminum alloy heat sink enclosure thermal conductivity debate, highlighting that the decision extends far beyond a single number on a datasheet.

| Parameter | Aluminum Alloy (e.g., 6063) | Copper (C11000) | Practical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Conductivity | ~200 W/m·K | ~400 W/m·K | Copper transfers heat from the source faster, reducing the core temperature rise. |

| Density | ~2.7 g/cm³ | ~8.9 g/cm³ | Aluminum housings are about one-third the weight, crucial for portable and mobile applications. |

| Raw Material Cost | Lower | Significantly Higher | Aluminum offers a lower bill of materials, affecting final product cost. |

| Ease of Manufacturing | Excellent for extrusion and machining. | More difficult to extrude; machines well but is gummier. | Aluminum allows for more complex, integrated, and cost-effective housing geometries. |

| Corrosion Resistance | Good (with anodizing) | Poor (requires plating/tinning) | Aluminum housings are more inherently stable in many environments. |

This comparison clearly shows that while copper wins on pure thermal performance, aluminum often provides the optimal balance when considering the holistic system requirements of weight, cost, manufacturability, and durability. The decision must be guided by answering a key question: Is the marginal gain in thermal performance from copper justify its substantial penalties in weight, cost, and processing complexity for this specific application? In many high-power but cost-sensitive commercial applications, the answer leans toward advanced aluminum designs.

Mechanical Design and Manufacturing Methodology

The physical architecture and construction method of the heat sink housing directly impact its thermal resistance, reliability, and suitability for the intended environment. Two primary manufacturing techniques dominate: extrusion and bonded fin construction, each with distinct advantages.

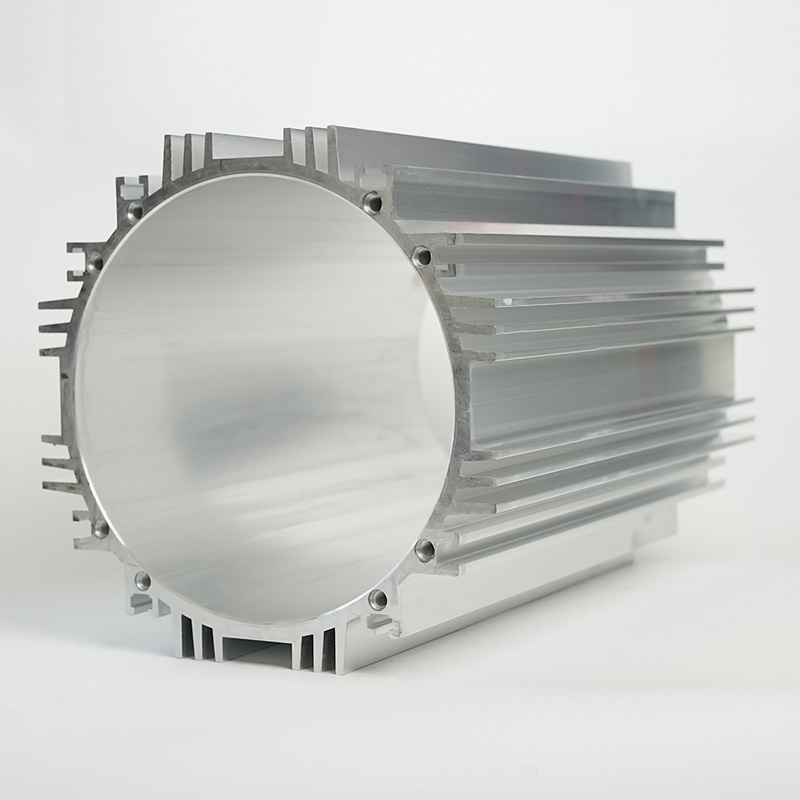

Extruded vs Bonded Fin Heat Sink Housing Performance

The manufacturing process defines the limits of a housing's geometry and, consequently, its cooling potential. Extruded housings are created by forcing heated aluminum alloy through a shaped die to produce a continuous profile, which is then cut to length. This process is highly efficient and economical for medium-to-high volume production. It excels at creating longitudinal fins that run the length of the housing, which are ideal for facilitating airflow in a single direction. The main thermal advantage of extrusion is the monobloc construction; the base and fins are a single, uninterrupted piece of metal, resulting in zero thermal interface resistance between them. This guarantees highly efficient heat conduction from the base up into the fins. However, extrusion is geometrically constrained by the physics of the process. The aspect ratio (fin height to fin gap) is limited, and it is challenging to create complex cross-sectional patterns or very thin, densely packed fins. This is where bonded fin technology shines. A bonded fin housing is assembled by attaching individually fabricated fins—which can be very thin and tall—to a separate base plate using a thermal interface material like epoxy or, more effectively, through a brazing or soldering process. This method offers unparalleled design freedom. Engineers can create optimized fin patterns with varying densities, incorporate different materials for the base and fins (e.g., a copper base with aluminum fins), and achieve much higher surface area-to-volume ratios. The performance comparison between these two methods is nuanced. For standard applications with consistent, moderate airflow, a well-designed extruded housing is often sufficient and more cost-effective. However, for applications demanding maximum heat dissipation in a confined space, or where airflow is highly directional and optimized, a bonded fin housing will typically outperform its extruded counterpart by providing greater surface area for convection. The critical caveat is the thermal integrity of the bond; a poorly executed bond can introduce a significant thermal barrier, negating the geometric advantages. Therefore, the choice hinges on the thermal density requirements, available space, budget, and the manufacturer's capability to produce a high-integrity bonded assembly.

Structural Integrity and Mounting Considerations

Beyond thermal performance, the housing must be a robust mechanical component. It must withstand vibrational loads, especially in transportation applications, without fatigue failure. It must also provide a stable, flat mounting surface to ensure proper contact pressure with the heat-generating component, as air gaps are the enemy of thermal transfer. The design must incorporate adequate structural ribs or features to prevent bending or warping under mounting force or thermal cycling. Furthermore, the mounting mechanism itself—whether it uses clips, screws, or specialized brackets—must be integrated into the housing design. The housing material's strength and the design's geometry must ensure that mounting forces are distributed evenly without causing deformation that could lift part of the base away from the heat source. This is particularly important for large-area housings covering multiple components. A holistic mechanical design ensures that the thermal performance promised by the material and fin design is fully realized in the field through consistent, reliable physical contact.

Integration with Cooling Systems and Environmental Sealing

A heat sink housing does not operate in isolation; it is part of a larger thermal management ecosystem that includes fans, air ducts, and potentially the external environment. Its design must facilitate, not hinder, this integration.

High Static Pressure Fan Compatibility with Heat Sink Housing

In many high-power applications, natural convection is insufficient, and forced air cooling via fans or blowers is required. The interaction between the fan and the heat sink housing is critical. A common mistake is pairing a high-performance fan with a housing that creates excessive airflow resistance, forcing the fan to operate inefficiently. This is where understanding high static pressure fan compatibility with heat sink housing becomes paramount. High static pressure fans are specifically engineered to push air through restrictive spaces, such as the dense fin arrays of an optimized heat sink. The housing design must be engineered in tandem with the fan's performance curve. Key factors include the fin density and length of the airflow path. A bonded fin housing with very high fin density will offer excellent surface area but will also be highly restrictive, mandating the use of a high static pressure fan. Conversely, an extruded housing with wider fin gaps creates less resistance and might be adequately served by a higher airflow, lower static pressure fan. The housing shroud or ducting, if present, must also be designed to minimize air leakage and turbulence, directing the maximum possible volume of air through the fin channels. Furthermore, the housing should guide the designer on optimal fan placement—whether in a push or pull configuration relative to the fins—to maximize heat exchange. Ignoring this compatibility results in increased noise, reduced fan lifespan, and, most critically, lower-than-expected cooling performance, as the fan struggles to move adequate air through the thermal core of the system.

IP Rating Standards for Sealed Heat Sink Enclosures

For electronics operating in harsh environments—outdoors, in industrial settings, or in vehicles—the heat sink housing often forms part of the product's environmental seal. In such cases, the housing transitions from a simple thermal device to a protective enclosure. This is where IP rating standards for sealed heat sink enclosures become a non-negotiable specification. The IP (Ingress Protection) code, defined by international standard IEC 60529, classifies the degree of protection provided against solid objects (like dust) and liquids. A common requirement for outdoor electronics is IP65, which offers complete protection against dust ingress and protection against low-pressure water jets from any direction. Designing a heat sink housing to meet such a rating presents unique challenges. The need for airflow to enable cooling directly conflicts with the need to seal the enclosure. Solutions often involve passive cooling through the housing walls (making material thermal conductivity even more critical) or the use of sealed air-to-liquid heat exchangers where the liquid loop is internal and the external radiator is sealed. If forced air is used internally, the housing must incorporate waterproof vents or membranes that allow air pressure to equalize while blocking water and contaminants. All seams, joints, and mounting points for fans or connectors must be sealed with gaskets or potting compounds. The selection of materials must also account for long-term exposure to UV radiation, moisture, and temperature extremes without degradation of the seal or the material itself. Therefore, when environmental sealing is required, the housing design becomes a complex exercise in balancing thermal performance, mechanical design, and material science to meet the dual mandates of cooling and protection.

Synthesizing the Selection Criteria for Optimal Performance

The journey to select the right heat sink housing is a systematic evaluation of interrelated factors, all converging on the specific needs of the application. It begins with a clear understanding of the thermal budget: the total heat dissipated, the maximum allowable junction temperature of the component, and the ambient operating conditions. This thermal requirement immediately informs the material choice—does the heat flux demand the superior conductivity of copper, or can a well-engineered aluminum solution meet the target? Simultaneously, spatial and weight constraints must be factored in, often nudging the decision toward aluminum or advanced composites. Next, the manufacturing method must be selected based on the required fin geometry and thermal density; a standard extruded aluminum profile might suffice, or the application may necessitate the advanced capabilities of a bonded fin design. The integration phase then forces critical decisions about airflow. Will cooling be passive or forced? If forced, the fin design and housing layout must be compatible with a fan's performance characteristics, particularly its static pressure capability, to ensure efficient system-level operation. Finally, the operating environment dictates the final layer of requirements. Does the housing need to provide environmental sealing to a specific IP standard, and if so, how does that alter the material choices, sealing strategies, and cooling approach? By methodically addressing each of these areas—material, manufacture, integration, and environment—and by considering the insights captured in long-tail keywords like aluminum heat sink housing design for power electronics and IP rating standards for sealed heat sink enclosures, engineers can move beyond a generic selection to a tailored, optimized solution. The correct heat sink housing is not the one with the highest thermal conductivity in isolation; it is the one that delivers reliable thermal performance within the complete set of mechanical, economic, and environmental constraints of the high-power electronic application it serves, ensuring stability, efficiency, and longevity in the field.

English

English Español

Español